The All American Flip Clock

The Ingraham flip clock by the McGraw-Edison Company, must be considered the great, all American flip clock. Not only was it one of the few, all American made flip clocks, on this one clock we find represented the names of three great Americans: Elias Ingraham, Thomas A. Edison and Max McGraw. While most will have some recollection of Thomas Edison, as time has passed, the other names have become somewhat obscure. We hope to fix this during this discussion and explain their connection.

To start we will review a very basic history of the three American names present on the clock, then follow this with a hands-on review of this All American Flip clock from the 1970s.

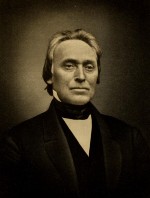

Elias Ingraham

For over 130 years, the Ingraham Company was a prominent family-operated US manufacturer of clocks and watches, with headquarters and plants located in Bristol, Connecticut. It was founded in 1831, when Elias Ingraham (who lived from 1805-1885) opened his own shop in Bristol as a cabinetmaker and designer of clock cases.

For over 130 years, the Ingraham Company was a prominent family-operated US manufacturer of clocks and watches, with headquarters and plants located in Bristol, Connecticut. It was founded in 1831, when Elias Ingraham (who lived from 1805-1885) opened his own shop in Bristol as a cabinetmaker and designer of clock cases.

Until about 1890, the company manufactured only pendulum clocks. During the 1890s, they began making lever escapement time clocks and alarm clocks. During the 1900s the company began production of 30-hour alarm clocks and pocket watches, including their version of the popular "dollar watch." This was a pocket watch for the working man which typically cost, one dollar. In 1930, The Ingraham Company started making wrist watches and in 1931 electric clocks.

By August 1942 the company had entirely re-tooled for production of critical war items for use during World War II, such as time-fuse parts for anti-aircraft and artillery weapons. Full production of clocks and watches resumed in 1946.

The Ingraham Company and name were sold to McGraw-Edison Company (which we will discuss in a moment) in November 1967.

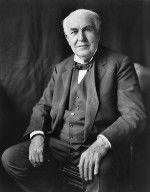

Thomas A. Edison

Thomas Alva Edison, widely known world-wide as America's greatest inventor was born in 1847 and died in 1931. Edison acquired a record number 1,093 US Patents over his lifetime and was the driving force behind such innovations as the phonograph, the perfection of the incandescent light bulb and the development one of the earliest motion picture cameras. For his work in the birth of the motion picture, Thomas A Edison actually has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Thomas Alva Edison, widely known world-wide as America's greatest inventor was born in 1847 and died in 1931. Edison acquired a record number 1,093 US Patents over his lifetime and was the driving force behind such innovations as the phonograph, the perfection of the incandescent light bulb and the development one of the earliest motion picture cameras. For his work in the birth of the motion picture, Thomas A Edison actually has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Edison practically invented a new mechanism for invention itself - what we would call today, the Research and Development Lab. He was one of the first to use a managed science and teamwork approach to the process of invention. Edison directed thirty companies under Thomas A. Edison Industries, Inc., employing over 10,000 workers in the design, prototyping and most importantly, commercialization of many new products.

Considered to be the first great Thomas Edison invention, and Edison's personal favorite, the early phonograph could record  the spoken voice and play it back. When speaking into the receiver, the sound vibration of the voice would cause a needle to create indentations on a drum wrapped with tin foil. The first recorded message was of Thomas Edison speaking “Mary had a little lamb.” Later Edison would use cylinders and discs for a more permanent storage of sound and music.

the spoken voice and play it back. When speaking into the receiver, the sound vibration of the voice would cause a needle to create indentations on a drum wrapped with tin foil. The first recorded message was of Thomas Edison speaking “Mary had a little lamb.” Later Edison would use cylinders and discs for a more permanent storage of sound and music.

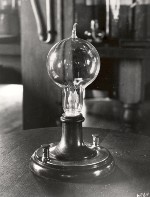

While historians agree that Thomas Edison was not actually the inventor of the electric light bulb, he was behind the development and production of the first commercially viable one. Earlier light bulbs were experimented with as far back as 1802, and over 20 other inventors had developed some sort of light bulb. But there was no question who was the driving force behind the lighting of America.

On Oct. 20, 1928, Thomas Alva Edison was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor – the nation’s highest award in recognition of services rendered.

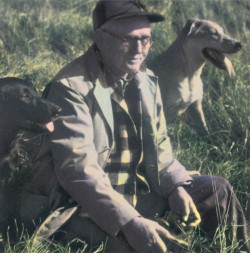

Max McGraw

And finally the great American entrepreneur who brought these names together - Max McGraw. Max McGraw was born in 1883 – and died suddenly on a hunting trip at age 81 on October 26 1964 (while still the head of the companies that he had founded).

And finally the great American entrepreneur who brought these names together - Max McGraw. Max McGraw was born in 1883 – and died suddenly on a hunting trip at age 81 on October 26 1964 (while still the head of the companies that he had founded).

At the young age of 17, Max McGraw started the McGraw Electric Co. in Sioux City, Iowa. From this modest beginning, McGraw established two of this country’s largest and most successful corporations at the time, McGraw-Edison Company and Centel Corporation. Centel Corporation was a telecommunications company, eventually acquired by Sprint, that provided basic telephone service, cellular phone service and cable television service.

The McGraw-Edison Company was created in 1957 through a merger of McGraw Electric and Thomas A. Edison, Inc, when that company was still being run by Thomas Edison's son, Charles Edison.

Due to the numerous acquisitions over the years of it's existence, the McGraw-Edison name became associated with a vast number household items from air conditioners, cooling fans, electric space heaters, air humidifiers, portable hair dryers, and other household appliances, not to mention many other electrical components for industry. And as mentioned earlier, The Ingraham Company was purchased by McGraw-Edison Company in November 1967. The Ingraham name, at the time very well known for quality American clocks, would eventually end up on modern time keepers by McGraw-Edison.

Side Note:

As Thomas Edison was behind the development and mass marketing of the first viable light bulb, Max McGraw was the driving force behind the development of the marketing of the first popular and profitable household toaster in the U.S, the Toastmaster.

The end of the McGraw-Edison Company

McGraw-Edison was subsequently acquired by Cooper Industries in 1985, which in turn was taken over by Eaton Corporation in 2012. Today, the McGraw-Edison brand can still be found on industrial, commercial, and institutional lighting products.

While the McGraw name may not be as prominent on electrical appliances as it was up until the mid-1980s, the legacy of Max McGraw lives on through his work in wetlands and natural resource conservation. In his role as an early conservationist, McGraw purchased over 1000 acres of land near his new plant in Elgin, Illinois and voluntarily established it as a protected wetlands - before that was even a thing (the protection of US Wetlands officially began in 1977). Curiously, it is said that McGraw's plant in Elgin converted some 1,000 loaves of bread into toast each day as part of its toastmaster development process. This toast reportedly was delivered to the wetlands to feed the water fowl. Clearly, Max McGraw, as an avid hunter, did not see hunting and fishing as being in opposition with conservationism, but rather, a part of it. To me, this calls to mind the earliest Americans - the Indians.

The McGraw Name Lives On

In 1962, McGraw established the Max McGraw Wildlife Foundation which today is recognized as one of the premier U.S research facilities for fish and wildlife management, as well as for conservation education. The Foundation sits on 1,250 acres of hardwoods, prairies, lakes and streams, near the Fox River in Dundee, Illinois, only 40 miles from Chicago, just north of Elgin, Illinois. The Max McGraw Wildlife Foundation mission statement: “Secure the future of hunting, fishing and land management through programs of science, education, demonstration and communication.”

In 1962, McGraw established the Max McGraw Wildlife Foundation which today is recognized as one of the premier U.S research facilities for fish and wildlife management, as well as for conservation education. The Foundation sits on 1,250 acres of hardwoods, prairies, lakes and streams, near the Fox River in Dundee, Illinois, only 40 miles from Chicago, just north of Elgin, Illinois. The Max McGraw Wildlife Foundation mission statement: “Secure the future of hunting, fishing and land management through programs of science, education, demonstration and communication.”

So you see, in this one Ingraham flip clock by McGraw-Edison, we have represented the names of three great Americans over a long period of American History, essentially from 1831 until 1985.

A Closer Look at the McGraw-Edison Ingram Flip Clock

The McGraw-Edison Flip clocks that I have available are the Ingraham Model 59-007 and the 59-008. We also have an Edison "digitalarm" Model 59-004. But we're going to mostly focus on the model 50-007. Primarily because I have it here in nearly new condition and secondly, because it looks awesome. There are other McGraw-Edison flippers out there, but not many more.

The McGraw-Edison Flip clocks that I have available are the Ingraham Model 59-007 and the 59-008. We also have an Edison "digitalarm" Model 59-004. But we're going to mostly focus on the model 50-007. Primarily because I have it here in nearly new condition and secondly, because it looks awesome. There are other McGraw-Edison flippers out there, but not many more.

The Ingraham flip clocks are quite angular from the sides and squared up tightly when looking straight on. The digits are notably bigger than most standard Japanese flip clocks of the era, and conspicuously absent from the digits is the word "Japan" on one of the minute tiles. The available colors, and especially the ones represented here, are classic 1970s.

To set the time on this clock you must slightly pull out on the knob as you rotate it clockwise. To set the alarm you allow the knob to move in towards the cabinet and rotate counter-clockwise. At first this seems to be a very efficient way to accomplish time and alarm setting, but in practice, it's just awkward to set the time. You have to maintain slight pressure outwards on the knob all the while turning. Perhaps a benefit of this is that a child probably wouldn't mess up your time setting (or damage the mechanism for that matter).

This model featured here has what the manufacturer calls the "Add-A-Nap Repeat Alarm." You simply push down when the alarm sounds for an extra 10 minute nap. This can be repeated up to 4 times. Then you're on your own.

The "Alarm Shut Off" arm is pulled to engage the alarm and pushed to shut off.

The more used Ingraham clocks will almost certainly have much of the chrome colored paint that borders the front elements of the clock worn away. As you can see this this model, much more of this striping is preserved.

Opening up the clock is a simple matter of pressing in at the middle of the side of the face of the clock, releasing a tab that connects to the clock's cabinet. After releasing one side, the front starts to easily move away from the cabinet.

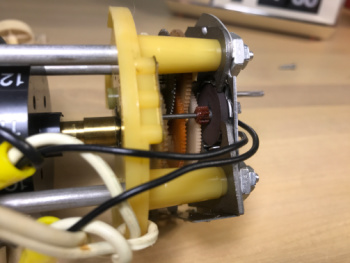

There's more room inside the clock then you might expect. This is primarily due to the relatively small electric motor utilized in these clocks. The motor is very simple, consisting of a metal disc positioned inside of a metal cage that is the cause of a rotating electric field. Curiously, due to the simplicity of the design, when the clock is energize this disc can as easily spin in the correct direction as can the wrong way. To prevent this motor's flywheel from spinning in the wrong direction the designers have fashioned a rotation stop device that will arrest the improper motion, the rebound from this event propelling the motor wheel in the correct direction.

There's more room inside the clock then you might expect. This is primarily due to the relatively small electric motor utilized in these clocks. The motor is very simple, consisting of a metal disc positioned inside of a metal cage that is the cause of a rotating electric field. Curiously, due to the simplicity of the design, when the clock is energize this disc can as easily spin in the correct direction as can the wrong way. To prevent this motor's flywheel from spinning in the wrong direction the designers have fashioned a rotation stop device that will arrest the improper motion, the rebound from this event propelling the motor wheel in the correct direction.

Complete disassembly of this clock is harrowing. What is called the "Time/Alarm Set Knob" is pressed firmly onto the rod that connects to the time and alarm gears of the clock. I think it may have initially been warmed up and pressed making a semi-permanent bond. Getting this off is best done by holding the rod with pliers from the inside of the clock then applying a firm outward force to remove the knob. It's a scary process and could possibly result in damage to the clock.

I have no intention of breaking down the newer clock, so an older version will get the rough treatment.

To get further into the clock you will have to remove the "Alarm Shut Off" arm by tilting the metal bar out of it's slot in the plastic arm. The alarm shut off works by not allowing the metal alarm bar to vibrate against the metal here in the clock after the alarm has been activated.

After tearing into the clock a little more you can see the simple flywheel of the motor, set in an equally simple cage.

Overall, what you have in the Ingraham flip clock is a perfectly fine 70s looking clock, but a clock that frankly could not compete with the mechanisms and motors being produced by the Japanese at that time.

Overall, what you have in the Ingraham flip clock is a perfectly fine 70s looking clock, but a clock that frankly could not compete with the mechanisms and motors being produced by the Japanese at that time.

Be that as it may, we still have to appreciate the history of this All American flip clock. All parts and pieces manufactured in the U.S.A and the clock assembled in-country as well. Personally, I would not feel that my flip clock collection was well-rounded without this clock.

Go to the Forum Post to comment